Thursday, December 26, 2013

Wednesday, November 20, 2013

On the whole, I do not find Christians, outside the catacombs,sufficiently sensible of the conditions. Does anyone have the foggiest idea what sort of power we so blithely invoke? Or, as I suspect,does no one believe a word of it? The churches are children playing on the floor with their chemistry sets, mixing up a batch of TNT to kill a Sunday morning. It is madness to wear ladies’ straw hats and velvet hats to church; we should all be wearing crash helmets. Ushers should issue life preservers and signal flares; they should lash us to our pews. For the sleeping god may wake some day and take offense, or the waking god may draw us out to where we can never return.--Annie Dillard

Tuesday, November 19, 2013

At each of life’s forkings a decision is made, and good fruit survives and grows only insofar as the buds of lesser fruit are deliberately clipped away. Happiness, the taste of good fruit, is therefore not the natural privilege of the uncultivated personality. It is, at least in part, an achievement.--CT Warner.

I am the true vine, and My Father is the vinedresser. Every branch in Me that does not bear fruit He takes away; and every branch that bears fruit He prunes, that it may bear more fruit. --Jesus

Haffner also speaks of the "automatic continuation of ordinary life that hindered any lively, forceful reaction against the horror" of Hitler. This may be true of many Americans as well, who see the erosion of freedom on a daily basis. Nevertheless — because they wake up in their own homes, eat the same cereal for breakfast, work at the same boring job to which they drive down familiar streets — they have a sense that everything is as it has always been. The fact that the legal structure, political protections, and other insitutions that guarded their freedoms are going, going, gone is nowhere near as real to them as are their daily routines.

In a 2002 review of Defying Hitler, Steven Martinovich commented, "The process [of statism] was so slow that one could almost understand how one day Germans walked the street as members of a shaky democracy and the next were prisoners. … Between those two days, the Germany [Haffner] grew up in both figuratively and literally disappeared."

--Review of Defying Hitler

Haffner also speaks of the "automatic continuation of ordinary life that hindered any lively, forceful reaction against the horror" of Hitler. This may be true of many Americans as well, who see the erosion of freedom on a daily basis. Nevertheless — because they wake up in their own homes, eat the same cereal for breakfast, work at the same boring job to which they drive down familiar streets — they have a sense that everything is as it has always been. The fact that the legal structure, political protections, and other insitutions that guarded their freedoms are going, going, gone is nowhere near as real to them as are their daily routines.

In a 2002 review of Defying Hitler, Steven Martinovich commented, "The process [of statism] was so slow that one could almost understand how one day Germans walked the street as members of a shaky democracy and the next were prisoners. … Between those two days, the Germany [Haffner] grew up in both figuratively and literally disappeared."

--Review of Defying Hitler

Saturday, November 16, 2013

You may not be able to order a beer in Iceland, but misunderstand someone as they're describing the regional elf lore, and you’re in luck. The expression “huh?” is practically universal, according to a recent study published in the journal PLoS One by researchers from the Max Planck Institute for Psycholinguistics in Nijmegen, the Netherlands.

Here’s why this is so unusual.

Most languages sound dramatically different from each other because words aren’t tied to what they stand for—dog and chien both represent a four-legged canine, for example—and each language is basically limited to a finite number of possible sound combinations.

“The likelihood that there are universal words is extremely small,” the authors write. “But in this study we present a striking exception to this otherwise robust rule.”

You may not be able to order a beer in Iceland, but misunderstand someone as they're describing the regional elf lore, and you’re in luck. The expression “huh?” is practically universal, according to a recent study published in the journal PLoS One by researchers from the Max Planck Institute for Psycholinguistics in Nijmegen, the Netherlands.

Here’s why this is so unusual.

Most languages sound dramatically different from each other because words aren’t tied to what they stand for—dog and chien both represent a four-legged canine, for example—and each language is basically limited to a finite number of possible sound combinations.

“The likelihood that there are universal words is extremely small,” the authors write. “But in this study we present a striking exception to this otherwise robust rule.”

Wednesday, November 13, 2013

In every important way we are such secrets from one another, and I do believe

that there is a separate language in each of us, also a separate aesthetics and

a separate jurisprudence. Every single one of us is a little civilization built

on the ruins of any number of preceding civilizations, but with our own variant

notions of what is beautiful and what is acceptable - which, I hasten to add, we

generally do not satisfy and by which we struggle to live. We take fortuitous

resemblances among us to be actual likeness, because those around us have also

fallen heir to the same customs, trade in the same coin, acknowledge, more or

less, the same notions of decency and sanity. But all that really just allows us

to coexist with the inviolable, intraversable, and utterly vast spaces between

us.”

― Marilynne Robinson, Gilead

― Marilynne Robinson, Gilead

The sun had

come up brilliantly after a heavy rain, and the trees were glistening and very

wet. On some impulse, plain exuberance, I suppose, the fellow jumped up and

caught hold of a branch, and a storm of luminous water came pouring down on the

two of them, and they laughed and took off running, the girl sweeping water off

her hair and her dress as if she were a little bit disgusted, but she wasn’t.

It was a beautiful thing to see, like something from a myth. I don’t know why I

thought of that now, except perhaps because it is easy to believe in such

moments that water was made primarily for blessing, and only secondarily for

growing vegetables or doing the wash. I wish I had paid more attention to it.

My list of regrets may seem unusual, but who can know that they are, really.

This is an interesting planet. It deserves all the attention you can give it.

--Gildead, Marilynn Robinson

Friday, November 1, 2013

The Vietnam Memorial Wall in D.C. contains the names of 58,272 Americans

who died in the war. Its message is that the tragedy of that wretched

war was that 58,000 Americans died. The wall is 146 feet long. Imagine a

wall that also contained the names of all the Vietnamese, Cambodians,

Laotians, and others who died. Such a wall would be over 4 miles long.

Saturday, October 19, 2013

Christ alone--of all the philosophers, Magi, etc.--has affirmed, as a principal certainty, eternal life, the infinity of time, the nothingness of death, the necessity and the raison d'etre of serenity and devotion. He lived serenely, as a greater artist than all other artists, despising marble and clay as well as color, working in living flesh. That is to say, this matchless artist, hardly to be conceived of by the obtuse instrument of our modern, nervous, stupefied brains, made neither statutes nor pictures not books; he loudly proclaimed that he made . . . living men, immortals.

Christ alone--of all the philosophers, Magi, etc.--has affirmed, as a principal certainty, eternal life, the infinity of time, the nothingness of death, the necessity and the raison d'etre of serenity and devotion. He lived serenely, as a greater artist than all other artists, despising marble and clay as well as color, working in living flesh. That is to say, this matchless artist, hardly to be conceived of by the obtuse instrument of our modern, nervous, stupefied brains, made neither statutes nor pictures not books; he loudly proclaimed that he made . . . living men, immortals.This is serious, especially because it is the truth.

Complete Letter of Vincent Van Gogh, p. 496.

Friday, October 18, 2013

"David Niven told the engrossing story (I had never heard it) of a

single episode in the chaotic flight from France after Dunkirk in 1940.

One motley assembly, ‘Royal Air Force ground personnel who were

trapped, Red Cross workers, women, ambulance drivers and, finally, the

embassy staff from Paris with their children — by the time they got to

St. Nazaire at the mouth of the Loire, there were over three thousand of

them and the British government sent an old liner called the Lancastria

to come and take them away, with three destroyers to guard her. They

were just pulling up the anchor when three dive bombers came. The

destroyers did what they could, but one bomb hit, went down the funnel

and blew a huge hole in the side, and she quickly took on a terrible

list. In the hold there were several hundred soldiers. Now there was

no way they could ever get out because of the list, and she was sinking.

And along came my own favorite Good Samaritan, a Roman Catholic

priest, a young man in Royal Air Force uniform. He got a rope and

lowered himself into the hold to give encouragement and help to those

hundreds of men in their last fateful hour.’ ‘Knowing he couldn’t get

out?’ ‘Knowing he could never get out, nor could they. The ship sank

and all in that hold died. The remainder were picked up by the

destroyers and came back to England to the regiment I was in, and we had

to look after them, and many of them told me that they were giving up

even then, in the oil and struggle, and the one thing that kept them

going was the sound of the soldiers in the hold singing hymns.’”

--Quoted in William F. Buckley, Jr., Nearer, My God: An Autobiography of Faith, page 209

--Quoted in William F. Buckley, Jr., Nearer, My God: An Autobiography of Faith, page 209

Saturday, September 28, 2013

Monday, September 23, 2013

Friday, September 6, 2013

My Church History

I was always aware of plural marriage and I knew that

Joseph had practised it. But when I first began to study the details, it

was by way of [an inadequately researched book that made startling claims], and I almost immediately encountered . . . [troubling] claims. . . . And I stopped at that point

because I hadn’t done the legwork to [know the whole story]. The author dumped it on me and he moved on and I had to decide what to

do with it, and many of you or most of you have perhaps had that

experience of kind of bopping along blissfully, and then someone

presents you with some stuff and just kind of leaves you to deal with

it. And that’s why plural marriage is such a useful tool for the antis

is because they don’t have to do much.

So, I thought about it a lot. And I didn’t know much but I knew three things.

- I knew that I didn’t know enough to answer the questions that this was going to bring up.

- I knew that finding the answers, if there were any, was going to take a lot of time and a lot of work.

- I knew that I might not be intellectually or spiritually up to the challenge of finding those answers or recognising the answers or being satisfied with the answers. And I knew that answers might not exist.

So, I determined then to take that to the Lord and it

was one of the most interesting experiences of my life. The scriptures

talk about having the Spirit give you words—give you words to pray when

you don’t know what you should say (e.g., Romans 8:26, 3 Nephi 19:24).

Well, I thought I knew what I was going to say, but apparently that

wasn’t what I was supposed to say, so I ended up saying something quite

different from what I knelt down intending to talk about. Somewhat to my

surprise, I found myself telling my Father in Heaven what bothered me

and instead of begging him for answers or insisting upon them (as I had

half planed to do) I found myself telling him that I would not forsake

him, that I would not forsake our relationship, that I was not going to

turn my back on it or on him. And, that I was not going to abandon my

covenants. I told him that come what may, I would do whatever he wanted

me to do. And then, I asked him if it would be spiritually dangerous for

me to commit the kind of time and energy and effort and intellectual

work that this project would probably require.

And I thought that that was going to be the first of

many struggling prayers over the issue. But God is gracious and he told

me very clearly that I was quite free to investigate it, that it would

all work out, though he gave me no idea of how or in what way, and that I

had nothing to worry about. And here I am, four years later, talking

about it—you must be careful what you ask for, you may get it. I almost

think he was a little bit unfair! If I had known this was part of the

deal—I did not bargain for this. I did not set out to be the person

people ask about plural marriage. Anyone out there who wants the title

can see me after.

But, as I’ve thought about that experience--and I think you picked that up very well in this quite heartrending letter that I’ve been reading from here—even the idea

of plural marriage is deeply hurtful for some people, especially women.

And it’s more, I’m convinced, than just some kind of social or cultural

revulsion. I think sometimes it’s speaks to the things that we have

experienced in our lives. It brings up memories of the abusive power or

of men who mistreated us or sexual abuse or inconsiderate spouses or a

host of other things. And it also is easily made to seem a textbook

example of the abuse of religion for power—the preacher who wants sex

with you and your daughter in exchange for salvation. And I sympathise

with all those reactions because I know something of them.

But, perhaps, because of them or in my case, because of

the vastness of the topic, we become very uneasy, in a way, with plural

marriage that I don’t see with other apologetic issues. We feel a

pressure and urgency to solve this problem above all others, once and

for all, and quickly. The more we look, the harder it seems to solve it.

In large part because the usual sources that we have to rely on, as I

have shown you, do very little to help us solve it. And without the

primary sources we are, in a sense, lost. And the cycle is thus a

vicious one because the more we try to solve it, the more it gets dumped

on us.

Now, I am not—before some mouth-breather on the internet concludes otherwise—I am not suggesting that we stop thinking or that I think thinking is a bad idea.

But, the problem was, in that moment, when I first

approached God with this, was that my spiritual life did not have four

or five years, which is how long I’ve been doing this now, to sit in the

church archives. My spiritual life could not be put on hold for that

long. How long could I halt between two opinions? If Joseph be Baal or a

sexual predator, don’t follow him. Jesus called the apostles and did

not tell them to spend three or four years with the primary sources

before deciding to answer the call to “Come, follow me.”

And for me, ultimately, the question (I see now) had

nothing to do with plural marriage at all. Plural marriage was only the

catalyst for a much more fundamental question and that question was, “Do

I trust Father?” And I see now, by the grace of God, that my

instinctive reaction was to do that, to express my trust and, amazingly,

to mean it. I did not realise it at the time, but what I effectively

chose to do, if I can put it crudely, is I chose to “consecrate my

brain.” I value my brain—we all do—nobody likes to be thought foolish or

naaive or ill-informed or duped or cognitively dissonant or any of the

other labels people can put upon us.

I’m a doctor, I’m regarded as a reasonably smart person, I love

science, I love evidence, I’m a sceptic, I’m a rationalist. I say all

this about myself—I am all those things, that’s part of how I conceive

of myself.

I could have gone before God and I could have demanded

answers, I could’ve told him I want the evidence and I want it now, I

want closure. I could’ve issued him ultimatums. I could’ve told him that

if this didn’t work out, I was quitting. But, I chose instead, to

consecrate my brain. I was willing to sacrifice my self-image, my years

of learning, my intellectual effort and my social respectability on the

internet (which I’m sure is crashing as I speak!) because I trusted

Father.

But, you know, it’s the funny thing about consecration,

you always get back everything you consecrate, with interest. Once my

Father and I had an understanding which took, maybe, 10 minutes, I was

back to thinking again. And immediately, I began to get more answers and

perspective that I know what to do with, and it hasn’t stopped yet.

It’s like trying to drink from a fire hose and I apologize for spraying

you all but I haven’t exactly got it controlled yet.

I got “good measure, pressed down, and shaken together,

and running over” (Luke 6:38). I cast my bread upon the water and God

sent back an aircraft carrier with a bakery on top.

My only fear in saying all this is that some people will

think I’m offering a pat answer—I’m not. Abraham was asked to

consecrate Isaac. And with Isaac went all the precious promises,

everything that made Abraham, Abraham. But he put his son on the altar

and he got him back and so much more. We know how Abraham’s story ends

but Abraham did not. And as Elder Maxwell observed, even when we know

it’s a test, we can’t say, “Look ma, no hands.”

You can’t consecrate your brain while crossing your fingers and hoping

that we can somehow trick God by going through the intellectual motions

and that he will support our demand for proof. You can’t ask for a sign,

but I bear you my witness that “signs follow them that believe,” in

this as in everything (D&C 63:9).

And so, I’ve tried to answer some questions today but I

will leave you with one. And that question is, “Do you trust Father?” If

you do, I have no worries, and if you do not, or if you’ve forgotten

how, or you fear you may be starting to, you must start there because no

answer from me or anyone else will satisfy you on a historical matter.

And if plural marriage doesn’t trip you up, something will. Settle it up

with Father and then you and I can talk.

Praise be to the man who communed with Jehovah. I will

not bear you testimony of the history I’ve told you for that could all

change tomorrow. But I bear witness of the Lord of the outstretched arm,

who comes into our nights and into our days and clasps us to his chest,

and who gives us back a hundredfold of all the poor leavings that we

drop upon the altar—sometimes with clenched fists and worried backward

glances, since we really didn’t want to give it up—that we drop upon the

altar which is already stained with his far more impressive sacrifice

on our behalf.

--Greg Smith (slightly edited)

Saturday, August 10, 2013

In his classic book Leisure: The Basis of Culture, philosopher Josef Pieper notes that “leisure in Greek is skole, and in Latin scola,

the English ‘school’.... ‘School’ does not, properly speaking, mean

school, but leisure.” He goes on to say that the Greeks did not have a

unique word for the more utilitarian notion of work: instead of saying,

as we do now, that “we live to work,” they said “we are unleisurely in

order to have leisure.”

Leon Wieseltier praised the tradition of the liberal arts, which were founded on leisure and contemplation. He told the graduates of Brandeis that the new “information era” came with dangerous consequences:

--Gergory Wolfe

Leon Wieseltier praised the tradition of the liberal arts, which were founded on leisure and contemplation. He told the graduates of Brandeis that the new “information era” came with dangerous consequences:

In the digital universe, knowledge is

reduced to the status of information. Who will any longer remember that

knowledge is to information as art is to kitsch—that information is

the most inferior kind of knowledge, because it is the most external? A

great Jewish thinker of the early Middle Ages wondered why God, if he

wanted us to know the truth about everything, did not simply tell us

the truth about everything. His wise answer was that if we were merely

told what we need to know, we would not, strictly speaking, know it.

Knowledge can be acquired only over time and only by method.

Wieseltier concludes by saying: “Perhaps culture is now the counterculture.”--Gergory Wolfe

Monday, July 1, 2013

.

On subjects of which we know nothing, we both believe and disbelieve a hundred times an hour, which keeps believing nimble.

— Emily Dickinson

— Emily Dickinson

Monday, June 24, 2013

But Then It Was Too Late

"To live in this process is absolutely not to be able to notice it—please try to believe me—unless one has a much greater degree of political awareness, acuity, than most of us had ever had occasion to develop. Each step was so small, so inconsequential, so well explained or, on occasion, ‘regretted,’ that, unless one were detached from the whole process from the beginning, unless one understood what the whole thing was in principle, what all these ‘little measures’ that no ‘patriotic German’ could resent must some day lead to, one no more saw it developing from day to day than a farmer in his field sees the corn growing. One day it is over his head.

"They Thought They Were Free--The Germans, 1933-45," Milton Mayer

"They Thought They Were Free--The Germans, 1933-45," Milton Mayer

Sunday, June 9, 2013

On Doing the Right Thing

“When faced with the prospect that we might have to give up some sin we have come to cherish dearly, we often say something like ‘I would rather die’” We’d rather die, it seems, because we see having our entire world collapse definitively as an easier task than the work of slowly reconstructing the world in fidelity to the call to repentance. Because life is work (the work to which grace spurs us), we’d rather give up our whole world than repent. But, as Jim [Faulconer] further notes, this is only because we don’t realize how much work we’re already doing in trying to keep our sinful world intact. We cherish a certain sort of work, the work of misery, and don’t want to give it up for a rather different kind of work. As Jim says: “One of the reasons God’s grace is required to save us is that when we are sinners, we cannot see life and death truly; we have distorted our vision so that life seems like death and death seems like life.”

--Joe Spencer on Jim Faulconer's "Life of Holiness"

--Joe Spencer on Jim Faulconer's "Life of Holiness"

Friday, June 7, 2013

On Doing the Right Thing

Once, I remember, I ran across the case of a boy who had been sentenced to prison, a poor, scared little brat, who had intended something no worse than mischief, and it turned out to be a crime. The judge said he disliked to sentence the lad; it seemed the wrong thing to do; but the law left him no option. I was struck by this. The judge, then, was doing something as an official that he would not dream of doing as a man; and he could do it without any sense of responsibility, or discomfort, simply because he was acting as an official and not as a man. On this principle of action, it seemed to me that one could commit almost any kind of crime without getting into trouble with one’s conscience. Clearly, a great crime had been committed against this boy; yet nobody who had had a hand in it—the judge, the jury, the prosecutor, the complaining witness, the policemen and jailers—felt any responsibility about it, because they were not acting as men, but as officials. Clearly, too, the public did not regard them as criminals, but rather as upright and conscientious men.

The idea came to me then, vaguely but unmistakably, that if the primary intention of government was not to abolish crime but merely to monopolize crime, no better device could be found for doing it than the inculcation of precisely this frame of mind in the officials and in the public; for the effect of this was to exempt both from any allegiance to those sanctions of humanity or decency which anyone of either class, acting as an individual, would have felt himself bound to respect—nay, would have wished to respect.

--Albert J. Nock's, "Anarchist's Progress"

The idea came to me then, vaguely but unmistakably, that if the primary intention of government was not to abolish crime but merely to monopolize crime, no better device could be found for doing it than the inculcation of precisely this frame of mind in the officials and in the public; for the effect of this was to exempt both from any allegiance to those sanctions of humanity or decency which anyone of either class, acting as an individual, would have felt himself bound to respect—nay, would have wished to respect.

--Albert J. Nock's, "Anarchist's Progress"

Tuesday, April 23, 2013

Kofa Mt., Arizona

If the stars should appear one night in a thousand years, how would men believe and adore; and preserve for many generations the remembrance of the city of God which had been shown! But every night come out these envoys of beauty, and light the universe with their admonishing smile.

― Ralph Waldo Emerson,

― Ralph Waldo Emerson,

Monday, April 15, 2013

One Art, by Elizabeth Bishop

The art of losing isn't hard to master;

so many things seem filled with the intent

to be lost that their loss is no disaster.

Lose something every day. Accept the fluster

of lost door keys, the hour badly spent.

The art of losing isn't hard to master.

Then practice losing farther, losing faster:

places, and names, and where it was you meant

to travel. None of these will bring disaster.

I lost my mother's watch. And look! my last, or

next-to-last, of three loved houses went.

The art of losing isn't hard to master.

I lost two cities, lovely ones. And, vaster,

some realms I owned, two rivers, a continent.

I miss them, but it wasn't a disaster.

—Even losing you (the joking voice, a gesture

I love) I shan't have lied. It's evident

the art of losing's not too hard to master

though it may look like (Write it!) like disaster.

so many things seem filled with the intent

to be lost that their loss is no disaster.

Lose something every day. Accept the fluster

of lost door keys, the hour badly spent.

The art of losing isn't hard to master.

Then practice losing farther, losing faster:

places, and names, and where it was you meant

to travel. None of these will bring disaster.

I lost my mother's watch. And look! my last, or

next-to-last, of three loved houses went.

The art of losing isn't hard to master.

I lost two cities, lovely ones. And, vaster,

some realms I owned, two rivers, a continent.

I miss them, but it wasn't a disaster.

—Even losing you (the joking voice, a gesture

I love) I shan't have lied. It's evident

the art of losing's not too hard to master

though it may look like (Write it!) like disaster.

Saturday, April 13, 2013

Primer on Mormon Prayer, by Adam Miller

A religious life is a life of prayer. Don’t skimp on this or, no matter how white your sepulcher, your insides will always just be full of dry bones.

How to pray:

1. Pray for at least twenty minutes, at least once a day, preferably in the morning.

2. Sit with your back straight, your hands nested in your lap, and your head only slightly bowed.

3. Aim for a 10-to-1 ration of listening to yammering. Given twenty minutes, say what you have to say in the first two minutes, then shut up and listen.

4. The Spirit can speak in all kinds of ways, but take as your baseline the classic Mormon expectation that the Spirit will manifest in your bosom or gut. Physiologically, direct you attention to the area just behind and below your navel. Simply attend, without interruption, to whatever bodily sensations show up there. Direct your attention to that single spot in waiting and expectation. This is what it means to “watch in prayer.”

5. Whenever your attention wanders – which it will do regularly, consistently, and almost immediately – note without judgment whatever you were daydreaming about (“Thinking about lunch-plans.” Or, “Thinking about the inconsiderate thing my husband did.”) and then, without elaboration, bring your attention firmly back to your gut and continue listening for the Spirit. You’ll get better with practice. But, in the meanwhile, you’ll also get a master-class in the content and extent of your own fallen, distracted, and profoundly self-absorbed nature.

6. The most obvious manifestations of Spirit include the following feelings in your bosom. Watch, in particular, for these: (1) warmth, (2) the rise and fall of your diaphragm in connection with the breath of life, (3) a spreading stillness, (4) a recession of your need, like the tide going out, to compulsively impose your will on the course of the day and on the people you’ll meet, (5) a willingness to, in general, pay attention and serve, and (6) the distinct impression that you are, in fact, regardless of circumstance, alive.

7. Learn how to pay attention to the Spirit in this same way throughout the day, as often as your able, whatever you’re doing. This is called “praying always.” The extension of this attentive, prayerful listening into the business of your daily life is the sum and substance of “conversion.”

How to pray:

1. Pray for at least twenty minutes, at least once a day, preferably in the morning.

2. Sit with your back straight, your hands nested in your lap, and your head only slightly bowed.

3. Aim for a 10-to-1 ration of listening to yammering. Given twenty minutes, say what you have to say in the first two minutes, then shut up and listen.

4. The Spirit can speak in all kinds of ways, but take as your baseline the classic Mormon expectation that the Spirit will manifest in your bosom or gut. Physiologically, direct you attention to the area just behind and below your navel. Simply attend, without interruption, to whatever bodily sensations show up there. Direct your attention to that single spot in waiting and expectation. This is what it means to “watch in prayer.”

5. Whenever your attention wanders – which it will do regularly, consistently, and almost immediately – note without judgment whatever you were daydreaming about (“Thinking about lunch-plans.” Or, “Thinking about the inconsiderate thing my husband did.”) and then, without elaboration, bring your attention firmly back to your gut and continue listening for the Spirit. You’ll get better with practice. But, in the meanwhile, you’ll also get a master-class in the content and extent of your own fallen, distracted, and profoundly self-absorbed nature.

6. The most obvious manifestations of Spirit include the following feelings in your bosom. Watch, in particular, for these: (1) warmth, (2) the rise and fall of your diaphragm in connection with the breath of life, (3) a spreading stillness, (4) a recession of your need, like the tide going out, to compulsively impose your will on the course of the day and on the people you’ll meet, (5) a willingness to, in general, pay attention and serve, and (6) the distinct impression that you are, in fact, regardless of circumstance, alive.

7. Learn how to pay attention to the Spirit in this same way throughout the day, as often as your able, whatever you’re doing. This is called “praying always.” The extension of this attentive, prayerful listening into the business of your daily life is the sum and substance of “conversion.”

met t' know ya

Consider, for example, the Jewish aristocrat and historian Josephus… who was sent, in AD 66, as a young army commander, to sort out some rebel movements in Galilee. His task, as he describes it in his autobiography, was to persuade the hot-headed Galileans to stop their mad rush into revolt against Rome, and to trust him and the other Jerusalem aristocrats to work out a better modus vivendi. So, when he confronted the rebel leader, he says that he told him to give up his own agenda, and to trust him, Josephus, instead. And the words he uses are remarkably familiar to readers of the Gospels: he told the brigand leader to `repent and believe in me’…

N.T. Wright

N.T. Wright

Monday, April 1, 2013

hey, like, whatever

Life narratives provide a bridge between developing adolescent self and an adult political identity. Here, for example, is how Keith Richards

describes a turning point in his life in his recent autobiography.

Richards, the famously sensation-seeking and nonconforming guitarist of

the Rolling Stones, was once a marginally well-behaved member of his

school choir. The choir won competitions with other schools, so the

choir master got Richards and his friends excused from many classes so

that they could travel to ever larger choral events. But when the boys

reached puberty and their voices changed, the choir master dumped them.

They were then informed that they would have to repeat a full year in

school to make up for their missed classes, and the choir master didn’t

lift a finger to defend them.

It was a “kick in the guts,” Richards says. It transformed him in ways with obvious political ramifications:

Richards may have been predisposed by his personality to become a liberal, but his politics were not predestined. Had his teachers treated him differently–or had he simply interpreted events differently when creating early drafts of his narrative–he could have ended up in a more conventional job surrounded by conservative colleagues and sharing their moral matrix. But once Richards came to understand himself as a crusader against abusive authority, there was no way he was ever going to vote for the British Conservative Party. His own life narrative just fit too well with the stories that all parties on the left tell in one form or another.The moment that happened, Spike, Terry and I, we became terrorists. I was so mad, I had a burning desire for revenge. I had reason then to bring down this country and everything it stood far. I spent the next three years trying to [mess] them up. If you want to breed a rebel, that’s the way to do it… It still hasn’t gone out, the fire. That’s when I started to look at the world in a different way, not their way anymore. That’s when I realized that there’s bigger bullies than just bullies. There’s them, the authorities. And a slow-burning fuse was lit.

Sunday, March 31, 2013

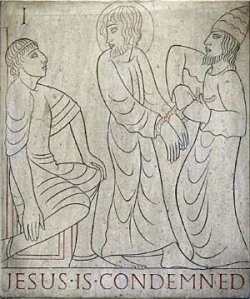

I Jesus is condemned to death

The very air that Pilate breathes, the voice

With which he speaks in judgment, all his powers

Of perception and discrimination, choice,

Decision, all his years, his days and hours,

His consciousness of self, his every sense,

Are given by this prisoner, freely given.

The man who stands there making no defence,

Is God. His hands are tied, His heart is open.

And he bears Pilate’s heart in his and feels

That crushing weight of wasted life. He lifts

It up in silent love. He lifts and heals.

He gives himself again with all his gifts

Into our hands. As Pilate turns away

A door swings open. This is judgment day.

--Malcolm Guite

"Halfway to poetry"

So wrote C.S. Lewis when describing “sentences that stick to the mind” from the prose of William Tyndale (c. 1494-1536).

What were these phrases? Here are two that Lewis singled out for special praise in his classic text, English Literature in the Sixteenth Century Excluding Drama —

We also hear echoes of Tyndale’s prose every day, throughout the English-speaking world.

Does that seem far-fetched? A simple presentation of Tyndale’s best-known phrases shows that it’s not. All are present in his celebrated translation of The New Testament, published in 1534. In Matthew, chapter five, we find “the salt of the earth.” Nine chapters later, in Matthew 16, we read of “the signs of the times.” Turn to Luke’s gospel, chapter twelve. There, we discover “eat, drink and be merry.” In Paul’s Epistle to the Romans, chapter 13, there is an admonition regarding “the powers that be.” And, in the Book of James, chapter 5, we encounter this memorable phrase: “the patience of Job.”

Our surprise only grows upon learning that Tyndale’s rendering of these phrases mark the first time they entered our language.

For people in the family of faith, the debt to Tyndale becomes greater. Do we love lines of scripture such as “Let there be light,” “seek, and ye shall find,” “fight the good fight of faith,” or “be not weary in well doing”? They come to us from Tyndale.

Tyndale translated The New Testament by himself—a staggering thought when one considers how many committees have undertaken the task in subsequent centuries. His was a beautiful flowering of scholarship and artistry, the more poignant because his work of translating the entire Bible was cut short by his tragic martyrdom.

Movingly, it’s been said that Tyndale’s translation, timeless and beautiful, bears the hallmarks of a “solitary music.” Today, though we scarcely know it, we are his fortunate heirs. The English we speak owes a great and lasting debt to his scholarship and sacrifice. Many cadences of our literature issued from his pen. More than 475 years have passed since his death. Bless God, we may hear his music still.

--Kevin Belmonte

What were these phrases? Here are two that Lewis singled out for special praise in his classic text, English Literature in the Sixteenth Century Excluding Drama —

Who taught the eagles to spy out their prey? even so the children of God spy out their Father, that they might see and love again.Then followed a succinct tribute, as memorable as it was evocative. In the best of Tyndale’s prose, Lewis concluded, “we breathe mountain air.”

Where the spirit is, there is always summer.

We also hear echoes of Tyndale’s prose every day, throughout the English-speaking world.

Does that seem far-fetched? A simple presentation of Tyndale’s best-known phrases shows that it’s not. All are present in his celebrated translation of The New Testament, published in 1534. In Matthew, chapter five, we find “the salt of the earth.” Nine chapters later, in Matthew 16, we read of “the signs of the times.” Turn to Luke’s gospel, chapter twelve. There, we discover “eat, drink and be merry.” In Paul’s Epistle to the Romans, chapter 13, there is an admonition regarding “the powers that be.” And, in the Book of James, chapter 5, we encounter this memorable phrase: “the patience of Job.”

Our surprise only grows upon learning that Tyndale’s rendering of these phrases mark the first time they entered our language.

For people in the family of faith, the debt to Tyndale becomes greater. Do we love lines of scripture such as “Let there be light,” “seek, and ye shall find,” “fight the good fight of faith,” or “be not weary in well doing”? They come to us from Tyndale.

Tyndale translated The New Testament by himself—a staggering thought when one considers how many committees have undertaken the task in subsequent centuries. His was a beautiful flowering of scholarship and artistry, the more poignant because his work of translating the entire Bible was cut short by his tragic martyrdom.

Movingly, it’s been said that Tyndale’s translation, timeless and beautiful, bears the hallmarks of a “solitary music.” Today, though we scarcely know it, we are his fortunate heirs. The English we speak owes a great and lasting debt to his scholarship and sacrifice. Many cadences of our literature issued from his pen. More than 475 years have passed since his death. Bless God, we may hear his music still.

--Kevin Belmonte

But most days, if you're aware enough to give yourself a choice, you can choose to look differently at this fat, dead-eyed, over-made-up lady who just screamed at her kid in the checkout line. Maybe she's not usually like this. Maybe she's been up three straight nights holding the hand of a husband who is dying of bone cancer. Or maybe this very lady is the low-wage clerk at the motor vehicle department, who just yesterday helped your spouse resolve a horrific, infuriating, red-tape problem through some small act of bureaucratic kindness. Of course, none of this is likely, but it's also not impossible. It just depends what you want to consider. If you're automatically sure that you know what reality is, and you are operating on your default setting, then you, like me, probably won't consider possibilities that aren't annoying and miserable. But if you really learn how to pay attention, then you will know there are other options. It will actually be within your power to experience a crowded, hot, slow, consumer-hell type situation as not only meaningful, but sacred, on fire with the same force that made the stars: love, fellowship, the mystical oneness of all things deep down.

--from David Foster Wallace commencement speech

Saturday, March 30, 2013

What kind of explanation of the development of these organisms, even one that includes evolutionary theory, could account for the appearance of organisms that are not only physically adapted to the environment but also conscious subjects? In brief, I believe it cannot be a purely physical explanation. What has to be explained is not just the lacing of organic life with a tincture of qualia but the coming into existence of subjective individual points of view— a type of existence logically distinct from anything describable by the physical sciences alone.

The existence of consciousness is both one of the most familiar and one of the most astounding things about the world. No conception of the natural order that does not reveal it as something to be expected can aspire even to the outline of completeness. And if physical science, whatever it may have to say about the origin of life, leaves us necessarily in the dark about consciousness, that shows that it cannot provide the basic form of intelligibility for this world.

--Thomas Nagel

The existence of consciousness is both one of the most familiar and one of the most astounding things about the world. No conception of the natural order that does not reveal it as something to be expected can aspire even to the outline of completeness. And if physical science, whatever it may have to say about the origin of life, leaves us necessarily in the dark about consciousness, that shows that it cannot provide the basic form of intelligibility for this world.

--Thomas Nagel

Consider a story from the life of D.L. Moody. As a fatherless boy raised in rural poverty, he was once sent several miles from home to work alongside an elder brother on a local farm. No more than ten, perhaps younger, he was overwhelmed with homesickness. Forty years later, as a world famous herald of the gospel, Moody frequently told this story. “It seemed,” he said, “that I was then further away from home than I had ever been before, or have ever been since.”

But then, one day, Moody and his brother were walking down the street of the town where they’d been sent to work. As Moody remembered—

"While we were walking down the street we saw an old man coming toward us, and my brother said, 'There is a man that will give you a cent. He gives every new boy that comes into this town a cent.' When the old man got opposite to us…my brother told him that I was a new boy in the town.

The old man, taking off my hat, placed his trembling hand on my head. He told me I had a Father in heaven.

It was a kind, simple act, but I feel the pressure of the old man’s hand upon my head today. You don’t know how much you may do by just speaking kindly.

But then, one day, Moody and his brother were walking down the street of the town where they’d been sent to work. As Moody remembered—

"While we were walking down the street we saw an old man coming toward us, and my brother said, 'There is a man that will give you a cent. He gives every new boy that comes into this town a cent.' When the old man got opposite to us…my brother told him that I was a new boy in the town.

The old man, taking off my hat, placed his trembling hand on my head. He told me I had a Father in heaven.

It was a kind, simple act, but I feel the pressure of the old man’s hand upon my head today. You don’t know how much you may do by just speaking kindly.

Happiness

There’s just no accounting for happiness,

or the way it turns up like a prodigal

who comes back to the dust at your feet

having squandered a fortune far away.

And how can you not forgive?

You make a feast in honor of what

was lost, and take from its place the finest

garment, which you saved for an occasion

you could not imagine, and you weep night and day

to know that you were not abandoned,

that happiness saved its most extreme form

for you alone.

No, happiness is the uncle you never

knew about, who flies a single-engine plane

onto the grassy landing strip, hitchhikes

into town, and inquires at every door

until he finds you asleep midafternoon

as you so often are during the unmerciful

hours of your despair.

It comes to the monk in his cell.

It comes to the woman sweeping the street

with a birch broom, to the child

whose mother has passed out from drink.

It comes to the lover, to the dog chewing

a sock, to the pusher, to the basketmaker,

and to the clerk stacking cans of carrots

in the night.

It even comes to the boulder

in the perpetual shade of pine barrens,

to rain falling on the open sea,

to the wineglass, weary of holding wine.

--Jane Kenyon

or the way it turns up like a prodigal

who comes back to the dust at your feet

having squandered a fortune far away.

And how can you not forgive?

You make a feast in honor of what

was lost, and take from its place the finest

garment, which you saved for an occasion

you could not imagine, and you weep night and day

to know that you were not abandoned,

that happiness saved its most extreme form

for you alone.

No, happiness is the uncle you never

knew about, who flies a single-engine plane

onto the grassy landing strip, hitchhikes

into town, and inquires at every door

until he finds you asleep midafternoon

as you so often are during the unmerciful

hours of your despair.

It comes to the monk in his cell.

It comes to the woman sweeping the street

with a birch broom, to the child

whose mother has passed out from drink.

It comes to the lover, to the dog chewing

a sock, to the pusher, to the basketmaker,

and to the clerk stacking cans of carrots

in the night.

It even comes to the boulder

in the perpetual shade of pine barrens,

to rain falling on the open sea,

to the wineglass, weary of holding wine.

--Jane Kenyon

Monday, March 4, 2013

The loveliest argument I know against unbelief was made by a woman whose name I have forgotten, quoted by the theologian John Baillie in Our Knowledge of God; it boils down to this: "If there is no God, whom do we thank?"

The force of this hit me on a mild November evening when I was oppressed by woes; I prayed for a little relief and tried counting my blessings instead of my grievances. I've long known that a great secret of happiness is gratitude, but that didn't prepare me for what happened next.

As I munched a cheeseburger, I could hardly think of anything in my life that couldn't be seen as a gift from God. As one of the characters in Lear tells his father: "Thy life's a miracle." Of whom is that not true?

The more we reflect on the sheer oddity of our very existence and, in addition, of our eligibility for salvation, the deeper our gratitude must be. Amazing grace indeed! To call it astounding is to express the matter feebly. Why me? How on earth could I ever have deserved this, the promise of eternal joy?

And given all this, in comparison with which winning the greatest lottery in the world is just a minor fluke, how can I dare to sin again, or to be anything less than a saint for the rest of my life?

Yet I know that my own horrible spiritual habits will keep drawing me downward every hour. Like most men, or maybe more than most, I am my own worst enemy, constantly tempted to repay my Savior with my self-centered ingratitude. When I think of my sins, the debt of thanksgiving itself seems far too heavy to pay. No wonder He commands us to rejoice. It's by no means the easiest of our duties.

--Joe Sobran

The force of this hit me on a mild November evening when I was oppressed by woes; I prayed for a little relief and tried counting my blessings instead of my grievances. I've long known that a great secret of happiness is gratitude, but that didn't prepare me for what happened next.

As I munched a cheeseburger, I could hardly think of anything in my life that couldn't be seen as a gift from God. As one of the characters in Lear tells his father: "Thy life's a miracle." Of whom is that not true?

The more we reflect on the sheer oddity of our very existence and, in addition, of our eligibility for salvation, the deeper our gratitude must be. Amazing grace indeed! To call it astounding is to express the matter feebly. Why me? How on earth could I ever have deserved this, the promise of eternal joy?

And given all this, in comparison with which winning the greatest lottery in the world is just a minor fluke, how can I dare to sin again, or to be anything less than a saint for the rest of my life?

Yet I know that my own horrible spiritual habits will keep drawing me downward every hour. Like most men, or maybe more than most, I am my own worst enemy, constantly tempted to repay my Savior with my self-centered ingratitude. When I think of my sins, the debt of thanksgiving itself seems far too heavy to pay. No wonder He commands us to rejoice. It's by no means the easiest of our duties.

--Joe Sobran

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)